ABSTRACT

Grounded in ethnographic observations, this article offers a commentary on the visible and invisible dynamics of mobility between China and West and Central Africa. It follows the transnational trajectories of African trader women and takes stock of some of the weight that these women shoulder during trips where goods and money are set in motion. The materiality of the transported consumer items shapes traders’ experiences of mobility and immobility. Trader women also must carry immaterial baggage relating to what their mobile, racialized female bodies represent to various people they encounter. Specifically, the Chinese state and general public view their bodies as threats to social order and, in the context of Ebola and COVID-19, as threats to public health. Our analysis also attends to the weight that female scholars metaphorically carry while conducting research. We devote space to addressing our presence as White researchers, thus attending to methodological opaqueness alongside issues of hidden geographies in transnational trade and migration.

基于人种学观察, 本文评论了中国与西非和中非之间流动性的有形和无形变化。追踪了非洲女商人的跨国轨迹, 评估了这些女性在货物和金钱流动的旅行中所肩负的重量。被运送的消费品的物质性, 决定了交易者的流动性和固定性体验。女性商人还必须携带非物质行李, 这些行李联系着其他人对流动的、种族化的女性身体的看法。具体而言, 中国政府和公众将其身体视为对社会秩序的威胁;在埃博拉和COVID-19背景下, 她们的身体则是对公共健康的威胁。我们的分析还关注了女性学者在开展研究时隐喻性地肩负的重量。本文讨论我们作为白人研究者的存在, 关注方法上的不透明性、以及跨国贸易和迁移中隐含的地理问题。

______________________________________________________________________

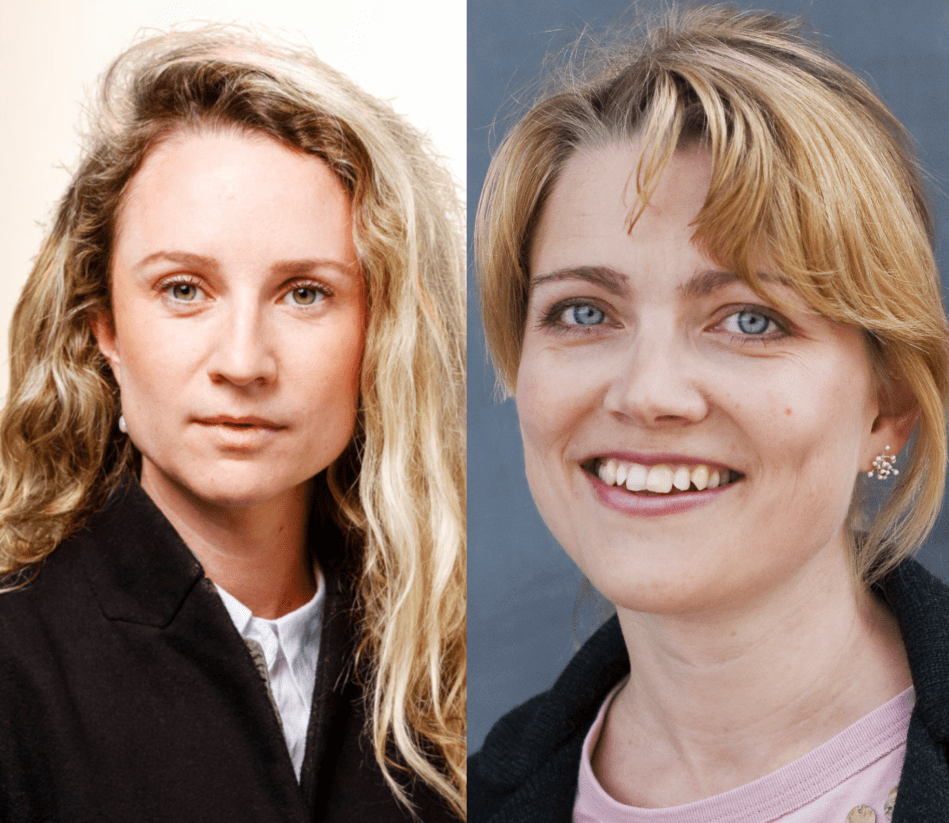

Situated in the context of the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, we, two White female researchers, have spent time getting to know communities of African trader women who consider themselves to be working “in the elsewhere.” In this transnational space, our experiences provided a basis for a shared sense of solidarity with our research participants but also highlighted our differences in manifold ways. Race and gender heavily shape social interactions in this fieldwork space—a dynamic that, when recognized, compels scholars to pay attention to the various ways in which their gendered and racialized identities affect how knowledge is produced. In fact, feminist methodologies insist on articulating the conceptual, theoretical, and ethical perspectives that constitute the foundation for knowledge production (Harrison 2009). Although female scholars historically have been more inclined to consider “how identity enriches the research process” (Nyantakyi-Frimpong 2021), more male researchers are adopting feminist approaches, acknowledging the relational aspects associated with their engagement and interaction with research participants.

Ongoing discussions about positionality in the disciplines of geography and anthropology have informed our thinking. This coauthored work does not endeavor to contribute directly to this concept but focuses on acts of positioning in our encounters and interactions with people in the field. Further, rather than accounting for positionality at the outset of the article and then moving on, we carry it with us throughout our analysis of entrepreneurial activities in China–Africa transnational spaces. As researchers, we are often one step behind in understanding the unfolding situations we take part in during data collection. Cultural encounters are “shifting processes” characterized by unequal power arrangements, yielding different outcomes for everyone involved (Robertson 2002, 790). The participants appearing in our research must also engage with processes of positioning as they respond to situations over which they sometimes have little control. As we attempted to strategically manage how we appear to others, the bodies with which we carried out our research became liabilities in unpredictable ways.

This article is based on multisited ethnographic research between China and West and Central Africa. We have both spent considerable time in Guangzhou among African transnational trader women, but never conducted fieldwork jointly. The first author has worked for several years in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), but has conducted only short-term research trips to Guangzhou since 2016, whereas the second author lived there with her family for over two-and-a-half years between 2009 and 2019 and made shorter research trips to West African countries. We carried out our respective fieldwork with different linguistic and disciplinary backgrounds, yet ended up with some similar experiences and interpretations that form the basis for this collaborative endeavor. As such, we use the first-person pronoun I to refer to either one of us.

In what follows, we analyze the strategies we deployed as White female researchers, as well as those used by African female traders through two concepts: weight and visibility. Here, we understand weight to mean material loads, such as the commodities for import, or the children we tie to our waist when we travel. It furthermore refers to the immaterial loads we carry, which are largely connected to our gender and race. For instance, part of our baggage comes with being women, because we are more vulnerable to gender-based harassment, which requires emotional labor and incurs practical inconvenience. Further, as researchers, we must also be aware of the ever-shifting power dynamics that require ongoing ethical decision making. Our own entry into African communities in southern China was aided by a racial otherness that we shared with our research participants. In that sense, we were all “others” in China, but this otherness is experienced very differently for White and non-White foreigners in many Chinese contexts.

In examining the visible and invisible baggage carried by both our research participants and ourselves, we are aware of the risks in drawing false equivalences. As White researchers, we carry a privilege in that we can benefit from the default position of power attached to whiteness, one that can be leveraged both consciously and unconsciously. This requires us to make visible the relations of power within each project. In what follows, we address how such inequalities and negotiable relations shaped our fieldwork in Guangzhou, a city where the political landscape and attitudes toward foreigners have undergone multiple changes over the past decade.

0 comments on “The Weight Women Carry: Research on the Visible and Invisible Baggage in Suitcase Trade between China and Africa”